Stewardship Blog

Interested in hearing about how the stewardship crew preserves our properties? Learn from them with this blog. Have specific questions? Contact us at info@thenatureinstitute.org or (618) 466-9930.

Restoration Workday

Would you like to get your hands dirty and help us remove invasive species? Join us for our Restoration Workday on Saturday, June 15th 9AM – Noon @ TNI Talahi Lodge.

Three Things to Look for on TNI Trails

Written by Eric Wright, TNI stewardship director

Three things to look for on the trails at TNI

The trails at The Nature Institute are back open and we want to thank you for your patience as the preserves were rested over the winter. While hikers were staying warm inside during the winter months, our staff worked diligently to improve our properties. Here are a few things to expect when you visit in 2019.

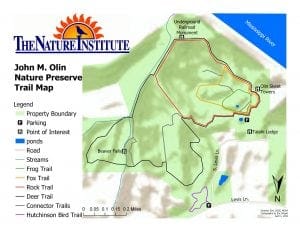

We sat down this winter and tweaked our trail map and trail signs. Hikers can now use our new map and trail signs to more easily create a multitude of hiking experiences. Like our old map, the locations of TNI’s landmarks are still noted, but hikers can now select a loop based on desired distance, time, and difficulty level. Trail intersections are marked with trail names and directional arrows. You can use the newly named Frog Loop to take a short stroll to see the hill prairie overlooking the Mississippi River, or you can commit a couple hours and tour the whole property on the Deer Trail.

Historically, wild fires periodically swept through our local ecosystems. Native plants evolved alongside these naturally occurring fires and adapted to survive and even benefit from these seemingly horrific events. Fire clears off dead growth from previous years causing some plant populations to decrease while causing others to increase as nutrients and space become available. Immediately after a burn, the land is literally black. Stewardship staff uses prescribed fire to mimic historical fire regimes. Despite wet conditions for most of the winter, we were able to perform multiple prescribed burns. Look out for invigorated growth in burned areas or a “top killed” tree or shrub as you cruise through the properties.

TNI has the full spectrum of invasive species known to our area plus a few that are only locally known. Invasive species outcompete and replace native species causing an overall reduction in biodiversity. Our goal at TNI is to promote high biological diversity within the habitats that we manage. The stewardship team has been aggressively battling bush honeysuckle, oriental bittersweet, Japanese hops and many more species for years. Evidence of this battle can be seen from the trails by observing the skeletons and stumps of fallen bush honeysuckle and the dangling dead vines of oriental bittersweet. As our native plants return in abundance, the evidence of this battle will begin to fade. Please enjoy as new areas can be seen from the trails and our native wildflowers return.

Now that the weather is beautiful and the trails are open, we hope you come out and explore. We bet if you keep your eyes open, you will find something you have never noticed before.

How Old is the Mississippi River?

Written by Eric Wright, TNI stewardship director

Age is an interesting concept. We’ve all met a young child that introduces themselves by saying, “Hi, my name is Emma. I’m 4 years old.” Early on, we learn our age affects our life and how others interact with us. Age, in human years, is concrete, well-documented, and easy to comprehend. We may not remember our own entrance into this world, but our parents and birth certificate can verify how long we’ve been around. Geologically, age is far more complex. Luckily, geologists have developed methods to help us deduce how and when geologic processes occur.

As I stared at the Mississippi River from atop our hill prairie at The Nature Institute (TNI), I asked myself, “How old is the Mississippi River?” I quickly realized that I was under-informed, and I don’t accept being under-informed. While searching for an answer, I traveled through time and discovered the remarkable events that have shaped and molded what lies beneath our nature preserves.

Bluff line where TNIs John M. Olin Nature Preserve stands, picture taken at Hoffman Gardens along the Great River Road, Route 100.

First, I want to throw out a qualifier. I am not a geologist by trade. I’ve utilized my resources to help create and fact check this blog post, but my interpretation may not be as thorough (or jargon laden) as the same story told by a professional geologist. The ability of geologists to reconstruct geologic history over a period of 4.6 billion years will always fascinate me. Please reference the sources at the end of this post for further reading.

We start our story about 1.4 billion years ago. During this time, also known as the Precambrian time, Illinois’ Precambrian basement was formed by the cooling of magma. Rock that is formed by the cooling of magma (underground lava) or by the cooling of lava is known as igneous rock. The Illinois Precambrian basement is composed primarily of granite and is located 2000 feet below the surface in northern Illinois and as deep as 17,000 feet below the surface in southern Illinois. Southern Illinois subsided (sank into the earth) over hundreds of millions of years.

Let’s skip ahead to 570 million years ago.

During the next several hundred millions of years, Illinois spent most of its time underwater. Sedimentary rock, rock formed by the deposition of sediments and organic matter with subsequent compaction, was formed during these years. The time period of particular interest to us is between 360 and 286 million years ago. During this time, Illinois was a shallow sea with a shifting coastline. Sediments and the remains of tiny shelled creatures dropped to the bottom of the inland sea and eventually formed Mississippian and Pennsylvanian limestones. These limestones can be seen as you gaze at the bluff faces along IL Route 100 (aka The River Road).

Beyond the beauty of our bluffs, the underlying limestone is also responsible for the sinkholes that occur throughout southwestern Illinois and on our properties. Rainfall absorbs carbon dioxide making water slightly acidic and capable of dissolving the minerals in limestone. Over time, the water carves out underground streams which form into caves. Sinkholes are formed when the caves beneath the surface collapse and/or subsequently pull rock and soil down into the caverns below.

From 286 million years ago to current day, most of Illinois remained above sea level preventing the formation of new sedimentary rock. Although we lack fossil evidence, dinosaurs roamed across most of Illinois during the Mesozoic era (245 – 66 million years ago). Erosion and multiple glaciations erased any fossil evidence of the dinosaurs. The supercontinent Pangea broke apart during the Jurassic period (208 – 144 million years ago) and the continents slowly settled into their current positions.

Now that the background has been covered, we can start talking about the age of the Mississippi River. I asked a few other biologists and even called a couple local museums in my search for answers. I received differing answers with marginal confidence. So, I dove deep into internet resources and borrowed several books from my local library. Still, I did not found a definitive answer. I decided that I must use my favorite multiple choice test strategy, the process of elimination.

Let’s travel back in time again to 286 million years ago…

when the last sedimentary rock layer was formed in Illinois. Outside of some technicalities, we can say that the Mississippi River was not formed while Illinois was under water.

Skip ahead to the Jurassic period when Pangea was being torn apart by plate tectonics: it’s hard to imagine the Mississippi River maintained its course through volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and shifting continents. In western North America, The Rocky Mountains were being thrust upward as late as 40 million years ago. Let’s make another assumption and assume that a mountain building event would move and reshape river systems across the entire continent. Therefore, the Mississippi River is less than 40 million years old.

Now, we are going to approach the question from the other direction. During the Illinoisan and Wisconsinan glaciations (300,000 to 10,000 years ago), glacial till and moraines created dams that rerouted the Mississippi River to the west. The former Mississippi River valley was later claimed by the Illinois River as the glaciers retreated. Unfortunately, this change in channel occurred upstream of us and therefore doesn’t help answer our question.

Between 5.3 and 2.4 million years ago, a major river system flowed from east to west across Illinois, through Missouri into Kansas, then south to the Gulf of Mexico. I’m going to assume (again) this ancient river flowed through the Mohomet River valley in central Illinois down the Illinois River valley to near St. Louis where it followed the Missouri River valley to Kansas City. At some point during this time period, the Mississippi was diverted near St. Louis to its current channel. Because of our location on this ancient river path, I will error on the side of caution and say the Mississippi River is at least 5.6 million years old.

To answer the question in the title of this blog post, the Mississippi River below the bluffs at TNI is between 5.6 and 40 million years old. Thirty-four million years may seem like a large window, but in the context of the 1.4 billion year window since the formation of the Precambrian basement, we have eliminated over 97% of the geologic time scale. Also, we discovered that the river below our bluffs at TNI could be one of the oldest stretches of the modern Mississippi River.

There wasn’t an easy answer to this seemingly simple question, but as I’ve heard before, “it’s more about the journey than the destination”.

References:

Wiggers, Ray. Geology underfoot in Illinois. Mountain Press Publishing, 1997.

https://isgs.illinois.edu/outreach/geology-resources/build-illinois-last-500-million-years

Don’t Let the Jargon Divide Us

As the new stewardship director, I have been tasked to write an occasional Stewardship Blog. The vagueness of this assignment and other biological knowledge that I have stuffed into my brain make this task more complicated than it seems. First, I have to consider my intended audience. Some readers may be fellow biologists, some may be bankers or mechanics, and some may be high school students interested in choosing a career similar to mine. That being said, anything I write must be approachable and easily understood by all.

A quick Google search tells me jargon is defined as, “special words or expressions that are used by a particular profession or group and are difficult for others to understand.” We all use jargon in our chosen professions and we are all guilty of forgetting that others may not know our special words. Further, when jargon ambushes us in a conversation, we are often afraid or embarrassed to stop the conversation to ask for a more complete explanation. This is why I have decided to discuss my life experiences with scientific jargon in my first blog.

My first real biology class was a general course specifically for biology majors. The long hours my professor had dedicated to earn her PhD had molded her into an intimidating a source of knowledge. As she thoroughly explained every topic, I instantly noticed that some of the words used were new to me. I may have heard them before, but I could not use most of these words in a sentence. Like any eager student, I put in the work and learned her language. The glossary of my biology text book became my new best friend. I remember having dinner with my dad and lightly venting about how, “the professor refuses to dumb things down so our class can understand.” (more…)